NUMBER 98

A blog about James Cooper of The Royal Newfoundland Regiment and one of the first five-hundred, and Newfoundland's links with Ayr

On the first of July 1916, in Beaumont-Hamel, France, my great-grandfather was one of 753 men who went over the top of a trench: heading straight into a vicious bombardment of enemy fire. Only 68 men survived. Less than one in every ten of the men who fought for their country and empire answered roll call the following morning. A chilling statistic that hit me like a tonne of bricks upon realisation how close the existence of myself and much of my family, very nearly came not to be. It must have taken everything he had to: avoid fatal fire, watch his comrades fall, pull himself out of the mud and make it back to base. The horrors of war not only define a moment in time; but also shape a modern world. In the case of my great-grandfather, James Cooper, regiment number 98 in the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, an entire family was shaped by the Great war. This is a story of war, tragedy, love and homecoming. This is the story of James Cooper.

Above: Joesph and Bridget Cooper. James' father and mother.

James was born June 1st, 1895, in St. John’s Newfoundland. The son of a fisherman, as many were in this part of the world, it was only natural that James follow suit. James’ grand-daughter, Jan recalls: “He used to talk of the seal hunting. He didn’t like it, but it was a way of life and had to happen. He said the Seals looked as if they had tears in their eyes as they were being clubbed”. A horrible thought indeed, yet life was so different one hundred years ago.

James had spoken of his anguish when the Titanic went down. The fishing boat he was on was so close to the gigantic ship, but it was so misty that fateful night, James and his fellow fishermen couldn’t see two feet in from of them; though they could hear.

When the Titanic sank in 1912, James would have been seventeen years old. We don’t know how long at that point James had been working on the boats. However, given that he could not read or write when he first came to British shores, it would seem he had very little formal education.

The destiny of James and many other young men all over the world over changed forever when war was declared, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the successor to the throne of Austria and Hungary, was assassinated by a Yugoslav loyalist in Sarajevo on 28th June, 1914. Austria declared war on Serbia with Germany offering support if necessary. Russia (allies of Serbia) mobilised and called on assistancefrom their French allies. This led to Germany declaring war on Russia and France. Britain declared war on Germany after its invasion of Belgium on August 4th.

Above: Artists impression, St. John’s, early 1900’s.

Below: St. John’s is the closest town to where the Titanic went down.

Newfoundland and Labrador is the youngest province in Canada. Newfoundland was organized as a colony in 1825, was self-governing from 1855–1934, and held dominion status from 1907–1949. In late 1948, the population of the two colonies voted 52.3% to 47.7%[17] in favour of joining Canada as provinces. Opposition was concentrated among residents of the capital St. John's, and on the Avalon Peninsula

Source: Wikipedia

Newfoundland, a British colony at the time and with a community identified as fiercely British, initially offered 500 recruits; “The first five-hundred” as they have come to be affectionately known. The RNDLDR website writes “On Saturday 3 October a large crowd gathered in St.John’s to watch the soldiers parade through the streets as they made their way to the harbour front where the troop ship had docked. At the pier was Governor and Lady Davidson, Premier Morris and members of both branches of the Dominion legislature.”

Supplies were scarce and materials hard to come by. As such, the first five-hundred donned a navy blue uniform, earning them a name they are known by to this day: “The Blue Puttees.” James’ wife, Margaret, used to tell her grand-daughter Jan, how she was vulnerable to the smart appearance of James, due to his blue puttee uniform and swagger stick. The Newfoundlanders were very smartly turned out, a principle James continued throughout his life. No-one knows what became of James’ swagger stick, though many years later, whilst working at an Ayr dairy, his son John, discovered a Swagger stick he believed to belong to another Blue Puttee who had settled in Ayr and had once owned the dairy. Unfortunately, the new owners wouldn’t let John return the stick to the family.

James was indeed one of the first five-hundred, signing up on opening day for enlistment, the 2nd of September 1914. After initial training at Mount Pleasantville, the newly founded regiment set sail for Plymouth, England on board the S.S Florizel, on October 4th. I have reason to believe, though it is unconfirmed at this point, that James’ father, Joseph was also on board the S.S Florizel with the first five-hundred, as a member of the crew.

Above: August, 1, 1914, a German officerannounces the Kaiser's order for mobilisation.

Above: First Five Hundred on board the S.S. Florizel, St. John’s, October 3, 1914

The following is an extract from “The Great War” Magazine, dated week ending October 7th 1916.

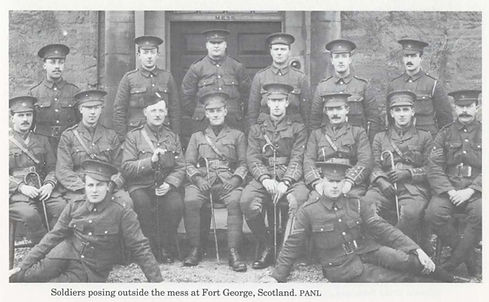

On first arriving in England, the Newfoundlanders were sent to Salisbury Plain and were quickly transferred to Fort George, Inverness-shire. English and Scottish people were at first apt to confuse the Newfoundlanders with the Canadian contingent, which had arrived about the same time, greatly to the annoyance of the Newfoundlanders, who were intensely proud of their land of origin.

From Fort George the young soldiers were sent for a time to Edinburgh, and then to Aldershot. Their strength was being steadily increased by fresh drafts from home. News came that the Canadians were off to France. Still the Newfoundlanders waited on, chafing at the delay. The war would be over, many of them feared, before they could strike a blow. They had only been asked to enlist for a year. Ten months of it were already over, and still they were in a peaceful camp in Britain, doing routine duty.

Then came a memorable day when Lord Kitchener came to review them and pronounced them “just the men I am wanting for the Dardanelles.” The soldiers were offered the choice of going back to Newfoundland, at the end of their year of service, or re-enlisting for the period of the war. Every man re-enlisted.

The regiment landed at Sulva Bay on September 16th and was at once attached to the 29th division, replacing the I/5th Royal Scots, who had suffered heavy casualties in recent engagements. The fact they were selected to take the place of so famous a corps was regarded as a signal honour.

This was the first real engagement in which the Newfoundlanders had taken part. They were soon, however, to undergo a much more severe experience. Towards the end of November, the Gallipoli Peninsula was swept by a storm of rain, wind, and snow. Trenches and dugouts were flooded. Men were overwhelmed where they stood, or frozen as they strove to struggle along. Hundreds of our troops were drowned in the flooded trenches; others died from exposure.

Above: World war 1 trenches

It was at this point that James and many other men suffered from a common virus from cramped, trench warfare known as dysentery. James saw no combat at Gallipoli due to the life threatening illness suffered by many of the Newfoundlanders, and would take time to recover before he could return to active service with his countrymen.

Below: James Cooper hospitalised somewhere in Europe. fourth bed on the right.

Above: From the “First five hundred” book

“The Great War” Magazine extract continues...

Then came the battle of the Somme. On the night of June 30th - July 1st the regiment marched eight miles from its billet to its allocated place in the trenches. The regiment reached its position about 2 AM on the morning of July 1st. Everyone knew that the mighty blow for which we had been preparing for months was now about to be delivered.

The Newfoundlanders were to have been used to push home the victory obtained by the first attacking parties. In place of that, word was sent that they were to make the third attempt to break the enemy line.

A heavy fire was concentrated on the German lines, and now came word for the Newfoundlanders to advance. Their Colonel called the company commanders together, and told them what was before them.There was no hesitation. With a cheer, every man jumped over the parapet. Again the German linessuddenly swarmed with men. They emerged once more from the dugouts in which they had remained sheltered. It seemed as though every concealed spot had a machine-gun behind it, and every machine gun was firing at once on our men.

Success was impossible. The terrific machine-gun fire was soon followed by shell fire. The men continued to move forward at rapid pace, without flinching. They fell by the units, by the score, soonby the hundreds. A few reached the begining of the enemy’s entrenchments, only to die there. Theyhad not even an opportunity to strike a blow at the foe. The whole thing was over so quickly that it seemed impossible that in a few minutes a gallant regiment should thus have been wiped out.

“When the order to attack was given,” the Corps commander, Liet-General Sir Alymer Hunter-Westonafterwards wrote to Sir Edward Morris, “every man moved forward to his appointed objective in hisappointed place, as if on parade. There were no waverers, no stragglers and not a man looked back. It was a mahnificent display of trained and disicplined valour, and the assualt only failed because deadmen can advance no farther. They were shot by machine-guns brought up by a very gallant foe under our intense artillery fire. Against any foe less well entrenched, less well organised, and above all - lessgallant, their attack must have succeeded.”

Jan recalls her grandfather James speaking of his sadness of the lives that were lost in those few minutes and seconds at the Somme. “He had a mustard gas scar running from the top of his breastbone to the bottom. The gun shot wound in his leg was an obvious bullet hole mark from one side to the other. He always said he was lucky that he did not lose his leg”. As to be exptected from a curious child, Jan would ask her grandfather if he had killed anyone during the war, “at that point the conversation was over. He didn’t want to talk about it."

Of course the effects of war and all the suffering encountered by the soldiers never left them. Jan remembers her Grandmother telling her of James’ “horrific dreams, night sweats and moments of withdrawing into himself.”

“The Great War” Magazine extract continues...

The story of the the Newfoundland men sent a thrill through the empire. General Hunter-Weston, addressing the survivors said, “Newfoundlanders, I saulte you individually. You have done better than the best.” In a letter to Sir Edward Morris, written shortly afterwards, the general repeated in even more emphatic terms his praise, “The Newfoundland Battalion covered itself with glory on July 1st by the magnificent way in which it carried out the attack entrusted to it.”

As it was, the action of the Newfoundland Battalion, and the other units of the British left, contributed largely to victory achieved by the British and French farther south, by pinning to their ground the best of the German troops, and by occupying the majority of their artillery, both heavy and field. The gallantry and devotion of this battalion, therefore, was not in vain, and the credit of victory belongs to them as much as to those troops farther south who actually succeeded in breaking the German lines.

Sir Douglas Haig was equally emphatic. In a message to the government of Newfoundland he wrote:“Newfoundland may well be proud of her sons. The heroism and the devotion to duty they displayed on July 1st has never been surpassed.”

When the news of the fight reached Newfoundland, the little colony was torn by conflicting emotions of pride and grief. There was scarcely a family of prominence that had not lost one near and dear to them in that fierce advance. “The soldiers of Newfoundland have won the highest praise which sons of Britain can ever earn,” said the governer. “The glory of it can never fade. July 1st, when our heroes fought and fell, will stand forever as the proudest day in the history of the loyal colony.”

Sir Edward Morris’s own description of his visit, taken from a published official report to the governer of Newfoundland: “I told them of the letter addressed to them by their lieutenant-general; how it was an heirloom that each man would transmit his children, a legacy establishing the honour, patriotism and characters of their fathers, of more value than gold and precious stones.”

Above: James was awarded the 1914-15 Star, British War & Victory Medals

Above: Certificate for Star medal.

Below: Certificate for British war and Victory medal.

Above: James’ discharge certificate.

Below: James and Margaret in their wedding photograph (Note: James has his swagger stick.

Above: Ayr high street, 1914.

Below: New York (date thought to be 1919).

As a result of James’ wounds at Beaumont-Hamel, the remainder of his service until after the war was over, consisted of lewis-machine-gun instruction. James was honourably discharged on December 7th 1918, allowing him to return home

When a war as grand as the scale of World War 1 occurs and soldiers are stationed in far-from-home lands and bases, it is inevitable that new relationships will form, which otherwise would simply not have happened. This was the case for James Cooper and Margaret Dunlop who met when James was stationed in Ayr along with his Newfoundland regiment. James and Margaret fell in love and married, as did an unknown many number of Newfoundlanders marry Ayrshire girls. Of course, when James and Margaret were married, the war was ongoing. Thus Margaret, like many millions of other wives, had to stay at home and worry for her husband’s safety; praying for his return.

However, even when the war was over, it was not so simple for James that he could return to Margaret, who had just given birth to their first child, Gladys. Upon his return to Newfound-land, James would have to work his passage back to Scotland. And so he resumed working on the fishing boats, earning as much as he could to seek passage back to Scotland.

I can’t imagine how heartbreaking it would be for James to miss out on the birth of his first child and her early life. For Margaret, it would equally be an emotional time, without the support of her husband, the father of her child,in a time when money was so very scarce. From James’ war records, there are letters from Margaret asking for monies owed. It is not known if Margaret ever received financial support from the Newfoundland government, though no doubt, James would be sending earnings from his work on the boats.

During this time, an opportunity of employment elsewhere would present itself. James had an uncle on his mother’s side who lived in New York and had managed to get James a job as a caretaker in the Carnegie library. James sent for Margaret and Gladys. However, Margaret did not want to leave her home, so James worked his passage back to Ayr where he would settle with his family, gaining employment with the gas board as a stoker. The Cooper/New York connection continued somewhat with James’ father gaining employment in the shipyards of Brooklyn. Unfortunately, tragedy struck when James’ mother Bridget drowned in Brooklyn docks in 1932. How sad for James, that he would have found out presumably by letter, some time after the fact, that his poor mother had died. Added to the fact that he could not attend her funeral, or have the opportunity to say goodbye. When Bridget died, her son would have been a man of 37 years, with a granddaughter, Gladys, then aged 14, and a grandson, John, then aged 11, who she never had the chance to meet. Records suggest James’ father, Joseph also died in New York, some time later.

One year after losing his mother, James and his wife were to encounter further tragedy when their fifteen-year-old daughter, Gladys, died after an outbreak of meningitis in the town. James gave up smoking in order to save up for a gravestone. He wouldn’t smoke again until his wife passed some 50 years later. Every Sunday, James, Margaret and John would visit the cemetery with fresh flowers for Gladys’ grave. The gravestone now also names James and Margeret, who were subsequently buried beside their daughter after their deaths, many years later.

The arrival of their first grandchild, Jan, some years later provided some comfort to the pain of losing Gladys. Jan’s memory of some of the stories she was told as a young child has been invaluable in terms of building a picture towards the story of James for his great-grandchildren such as myself. Jan recalls being told of the story of the Colonel of the regiment’s horse who wouldn’t go past a certain cottage without being fed by the lady of the cottage. This story is also in Fighting Newfoundlander book.

We were surprised, yet amused to find in James’ war records that he had been summoned and warned about missing a parade due to drinking alcohol. Indeed the Fighting Newfoundlander book recalls the Newfoundlanders as being prone to a drink or two, to put it lightly. The horrors of war would surely drive even a sober man to the relaxation comforts of a whiskey or beer, no doubt.

My Mother Jacqueline recalls her Papa never being the same again after her Nana died: “He used to slouch in his chair and would often stare into space. He lived for her.”

On the day of her funeral, James wore a smart hat with a feather. He removed it from his head and threw it into the grave after her coffin. An act that showed he felt life had finished.

Left: Gladys in the last known photograph before her death

Below: Margaret with her children, John and Gladys.

However, life had not finished for James. His life was to reach full cirlce with a trip back to his native homeland with his son John, shortly after Margaret died. After wanting to return for so long, James did so, a visit 50 years in the making.

The trip was supposed to only be for two weeks, however James and John missed the return flight, arriving at the airport as the plane was taxing down the runway. Thus they had an extra week for family reunion, as the flights were only once a week in those days.

It has been said, although unconfirmed, that the reason James and John were late to the airport was due to a final drink before they left. This definately sounds like a Cooper trait to me.

James died on 30th January 1981, at the magnificent age of 85. Most likely he was the last surviving of the Blue Puttees in Ayrshire, and perhaps in Britain.

Descendants of James and Margaret are:

Grand Children: Jan Gladys Cooper; Jacqueline Cooper: Michael Cooper: Lorna Cooper.

Great Grand Children:Jillian Hall; Jennifer Sands; Heather Sands; Iaian Sands; Calum Sands; John Cooper; James Cooper; James Brown.

Great Great Grand Children: Madelaine Hall, Susannah Hall, Isla Sands, Jack Sands.

Note: It is my intention that this blog post be updated regularly as new information comes to light and accuracy confirmed.

Please see acknowledgments section for links and credits.I have written James' story with the best of intentions of maintaining accuracy. Please contact me if any errors need corrected.

Additionaly, I would like to hear from any other surviving relatives of The BluePuttees, from Ayrshire or abroad. Please get in touch.

Above: [top l-r] John Cooper [James' son from Ayr Scotland] , Edward Cooper , William Cooper [bottom l-r] James Cooper and Julia CooperAll Brothers and Sister of James Cooper from St John's, Newfoundland

Below: James receiving his gold watch upon retirement.